The Dead Supreme

— Scott Covert

4th May, 2024 — 15th June, 2024The Dead Supreme

4th May, 2024 — 15th June, 2024 , Galerie Allen

The Dead Supreme

4th May, 2024 — 15th June, 2024 , Galerie Allen

The Dead Supreme

4th May, 2024 — 15th June, 2024 , Galerie Allen

The Dead Supreme

4th May, 2024 — 15th June, 2024 , Galerie Allen

The Dead Supreme

4th May, 2024 — 15th June, 2024 , Galerie Allen

The Dead Supreme

4th May, 2024 — 15th June, 2024 , Galerie Allen

Wilde, 1996-2022

oil painting stick and permanent oil pastel on acrylic on muslin

200 x 200 cm

Photo: Aurélien Mole

Courtesy the artist and Galerie Allen, Paris

Composition Green, 1996-2022

oil paint stick and permanent oil pastel on acrylic on muslin

200 x 200 cm

Photo: Aurélien Mole

Courtesy the artist and Galerie Allen, Paris

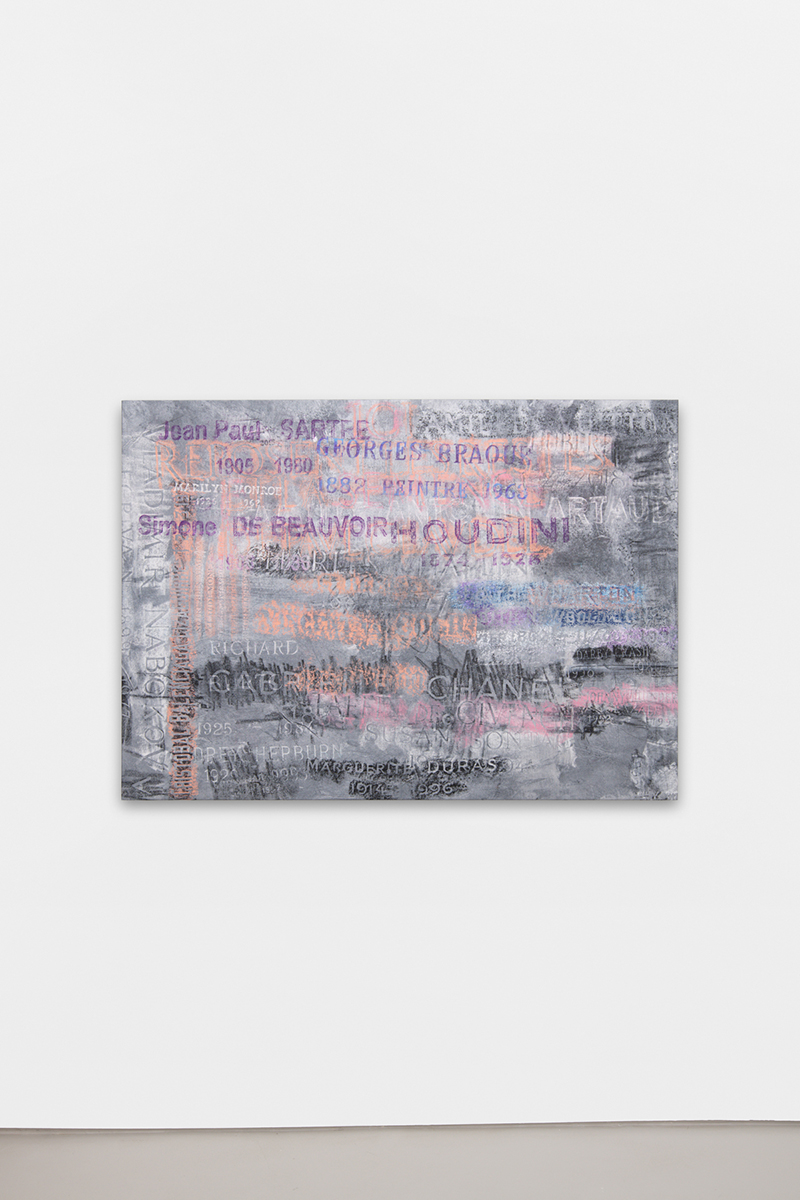

France, 2023

oil painting stick and permanent oil pastel on acrylic on muslin

105 x 146 cm

Photo: Aurélien Mole

Courtesy the artist and Galerie Allen, Paris

Red Composition, 2017-2024

oil painting stick and permanent oil pastel on acrylic on muslin

129 x 140,5 cm

Photo: Aurélien Mole

Courtesy the artist and Galerie Allen, Paris

Painters, 1996-2024

oil painting stick and permanent oil pastel on acrylic on muslin

130 x 140 cm

Photo: Aurélien Mole

Courtesy the artist and Galerie Allen, Paris

The Warhols, 2010-2024

oil paint stick and permanent oil pastel on acrylic on muslin

80 x 80 cm

Photo: Aurélien Mole

Courtesy the artist and Galerie Allen, Paris

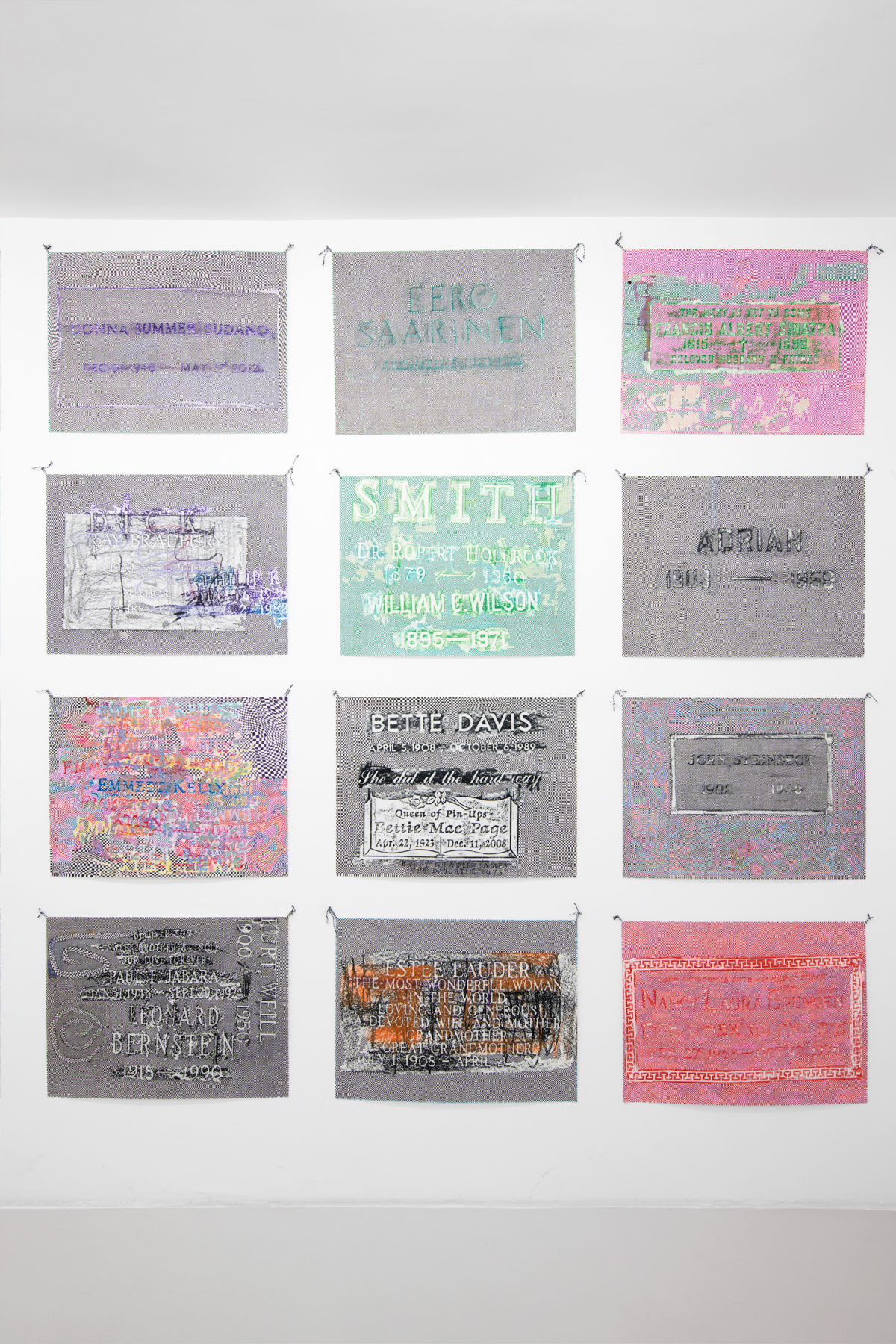

Queens, 2024

oil paint stick and permanent oil pastel on acrylic on linen

75 x 70 cm

Photo: Aurélien Mole

Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Allen, Paris

Musical Composition, 1996-2024

oil paint stick and permanent oil pastel on acrylic on muslin

140 x 126 cm

Photo: Aurélien Mole

Courtesy the artist and Galerie Allen, Paris

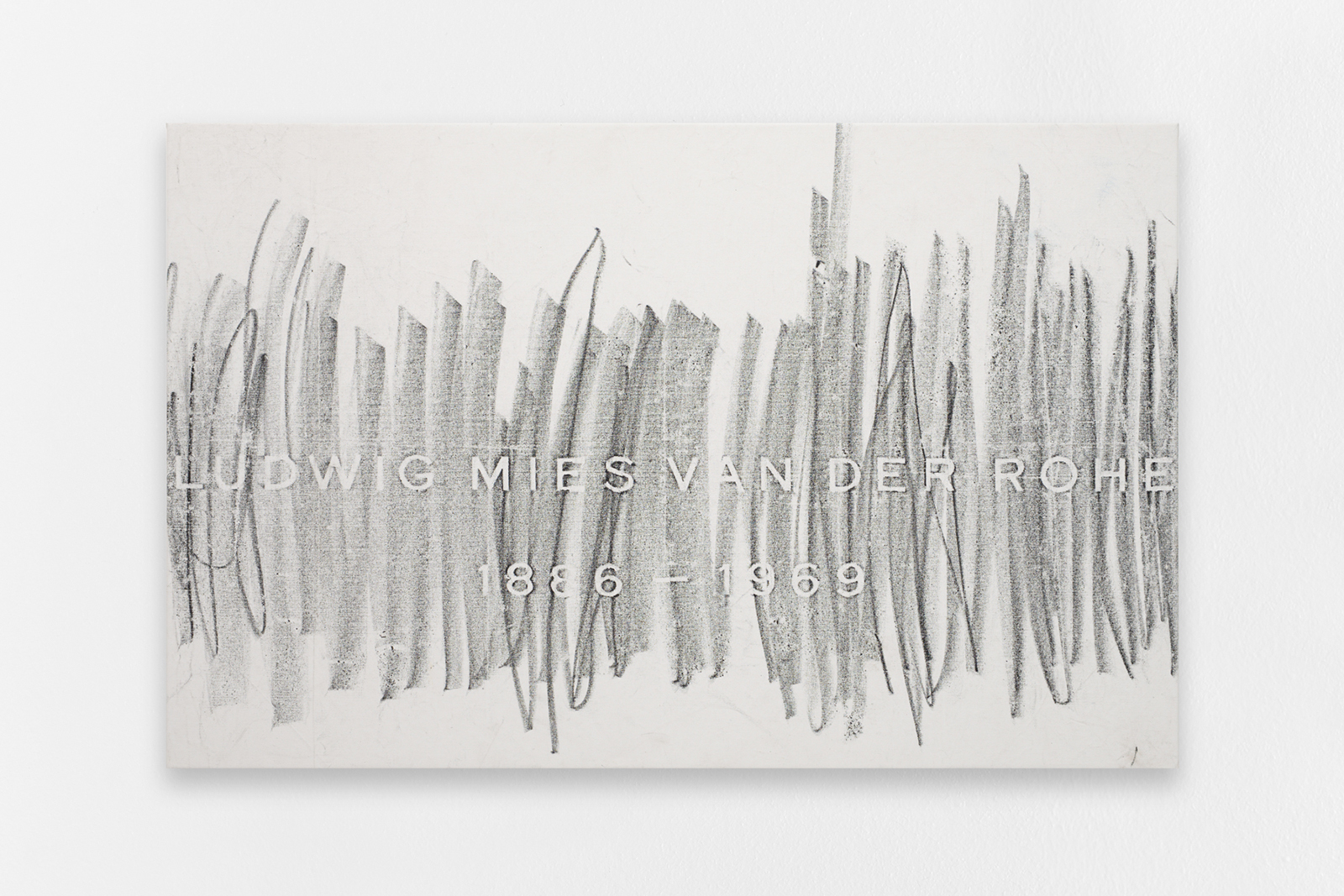

Mies Van der Rohe (white), 2022

oil paint stick and permanent oil pastel on acrylic on muslin

77 x 123 cm

Photo: Aurélien Mole

Courtesy the artist and Galerie Allen, Paris

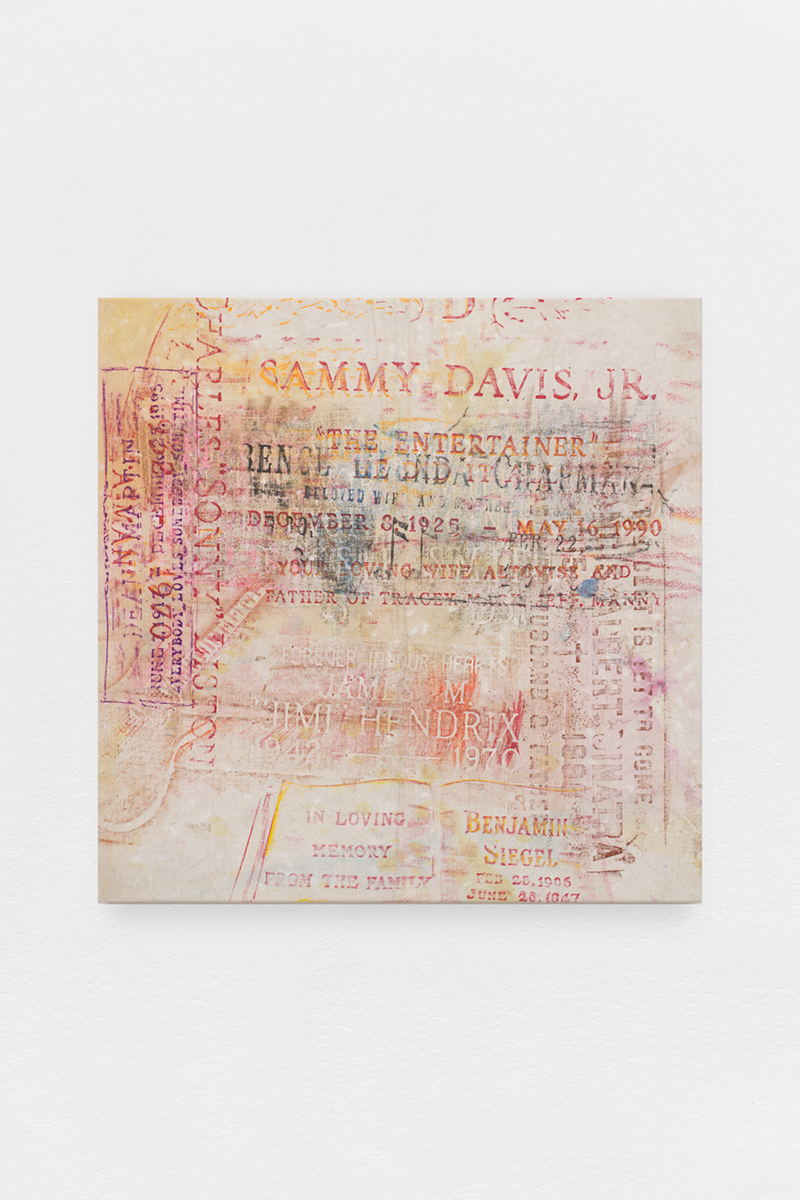

Little Sister - (The entertainer), 1996-2000

oil paint stick and permanent oil pastel on acrylic on muslin

69 x 67 cm

Photo: Aurélien Mole

Courtesy the artist and Galerie Allen, Paris

Press release

“I have to go.”

“Where?”

“Colombia.”

“Who’s there?”

“Pablo Escobar…and then I neeeeeed to go to Poland for Wojciech Frykowski, and then I have to go to Australia to get Leigh Bowery.”

To get, to get, to get…Scott Covert is a collector; of names, of places, of what he calls, “people of character.” He also loves deplorables, along with kings, queens, kidnappers, politicians, ballerinas, murder victims and actresses. Looking at a Scott Covert painting is like playing a game of Where’s Waldo? or Où est Charlie?, a search to find people buried within the palimpsests that have accrued over decades. Each work is a record of a journey, a pilgrimage made by the artist to see the dead wonders of the world. These cemeteries are his studio, his car is his storage space, filled with loose canvases splayed across the seats. For 39 years, Scott Covert has been carrying out this time-based artwork.

Going to a cemetery with Scott Covert is a singular experience. His name is an aptronym: Covert. He goes in and out of mausoleums carrying bags packed with works in progress, and sometimes blank slates, (“virgins” he calls them). Sometimes he also brings a ladder. You might have to stand lookout, make sure no guards or mourners are poking around. If you have a steady hand, you can help hold the canvas in place, as he frenetically pulls the names, dates and dashes from the stone. With each rubbing, Covert plucks history makers out from their final resting place and brings them back into the world’s circulation. The action is like a resuscitation, giving a new kind of immortality to their memory.

The art of grave rubbing is as timeless as death itself. Since antiquity, people have been lifting impressions from funerary stone reliefs. In China, the recorded history of grave rubbings stretches back to the Tang Dynasty. In the West, the tradition was revived by the Victorians and American New Englanders, whose fascination with death made cemeteries a gathering place for picnics and recreation. Like Covert however, people in the 19th century did always not consider the subject of death to be morbid, but rather, something appealing. In masterworks such as Pre-Raphaelite John Everett Millais’ Ophelia, 1851-52; Henry Wallis’ The Death of Chatterton, 1856-58, and Robert Browning’s Porphyria’s Lover, 1836, death became sexy, indulged in what philologist Alexander Welsh calls, “radiant idleness.” The seductive reframing of pathos allowed for the withdrawing of life to become a spectacle of love and desire. This conception of death as romantic may have acted as a palliative; mourning was not an experience of loss, but of transcended purity. For Scott Covert, death is similarly not a fearsome subject: “I’m not afraid of death. It makes life so much more interesting.” To die young is to die beautiful, full of potential and the excitement of what can never be realized. These artworks are a celebration of lives lived fully, with all the excitement and tragedy that entails.

As to where Covert’s Dharmic-like acceptance of death stems from, living through the 1980s and ‘90s AIDS Epidemic may provide something of an explanation. As a gay male artist and then-drug user living in the East Village, Scott Covert watched his friends unceremoniously die in droves. And while he became a regular on the funeral circuit, he miraculously escaped attending his own.

In 1978, Covert had arrived in New York from San Francisco, where he had taken classes in acting and studio art, but dropped out after one semester, finding the academic model too restrictive. He decided instead to pursue his passion for acting, working as the first male usher on Broadway and ingraining himself in the theater world. Following the performances, Covert would make his way back downtown to the East Village, where crime was high and rent was cheap; consequently, it was a haven for young artists. After midnight, art and music coalesced with dance parties segueing into vaudeville performances, film screenings and pop-up art exhibitions at venues like Club 57, Danceteria, Mudd Club and The Saint. Here, Covert performed in a number of utterly camp, iconoclastic adaptations of Broadway shows such as Bye, Bye Birdie, Peter Pan and Boeing Boeing.

However, the most critical performance Covert gave was in an adaptation of Henrik Ibsen’s play Ghosts, directed by actor Andy Rees. Rees’ remaking of the 19th century play was set in the present and switched Ibsen’s original storyline of a son dying of syphilis with that of a son (played by Covert) suffering from a mysterious illness. At the time of the show’s performance in 1982, this unnamed disease had just been given the medical term, Auto Immune Deficiency Syndrome, also known as AIDS. Ghosts has since come to be known as “the first AIDS musical.” The disease decimated the downtown art scene and shuttered it’s creative spirit, taking the lives of artists including: Keith Haring (1958-1990), Robert Mapplethorpe (1946-1989), Cookie Mueller (1949-1989), Jimmy DeSana (1949-1990), Ethyl Eichenberger (1945-1990), John Sex (1956-1990), Peter Hujar (1934-1987), Klaus Nomi (1944-1983) Adolfo Sanchez (1957-1990), Jack Smith (1932-1989), Tseng Kwong Chi (1950-1990), David Wojnarowicz (1954-1992), Martin Wong (1946-1999) and countless others. Scott Covert, blessed with nine lives, continues to honor his many lost friends. (That is, minus those that befell what in Covert’s eyes, is the ultimate tragedy: not being buried!)

Covert calls himself The Dead Supreme. As a boy: white, gay, Catholic, and growing up in suburban New Jersey; while all the kids at school were deciding whether they favored The Beatles or The Rolling Stones, he loved The Supremes. But while most Motown fans worshipped Diana Ross, he had a soft spot for Florence Ballard: the one who was kicked out for being an alcoholic and died penniless. In 1985, his sympathy for Flo led him to Memorial Park Cemetery,

There I was…standing in Warren, Michigan, 13 Mile Road. It’s Section D when you enter between two roads…It’s on a mound, she rests at the top in the center. Florence had been married when she died, and the stone said ‘Florence Glenda Chapman, June 30, 1943–February 22, 1976.’ A brass marker lay flat on the ground. I placed a sheet of paper on it, wiped my crayon across the paper to capture the name and dates. The paper shifted. I didn’t want it to become muddled, so I took another crayon, a different color, to finish it. The second color made it pop, and when I looked at it, I heard that little bell that Gertrude Stein writes about. I’ve been doing it ever since.

Text by Ariella Wolens

Scott Covert is an American artist born in 1954 in Edison, New Jersey. He lives in New York and works on the road. In 2022, his retrospective, Scott Covert: I Had a Wonderful Life was held at NSU Art Museum Fort Lauderdale in Florida. The exhibition was followed by his show, C’est La Vie, at Studio Voltaire in London, England. Recent solo presentations have also been held at Derek Eller Gallery, New York and Parker Gallery, Los Angeles, 2023. Covert has been the subject of articles published in Artforum, Mousse Magazine, The Paris Review, Ursula and The Guardian.